Is the West Turning on Nigeria Over Its French Tilt?

By Babafemi Ojudu

Nigeria’s foreign relations have never existed in a vacuum. Our geopolitical identity was shaped long before independence — indeed, long before the idea of Nigeria itself crystallized. When European powers gathered in Berlin in 1884–85 to partition Africa, the territories that would later form Nigeria were effectively allotted to Britain. That historical act — distant yet decisive — placed Nigeria within the British sphere for decades to come.

From the Royal Niger Company’s commercial dominance to Lord Lugard’s 1914 amalgamation, British rule constructed the administrative and political scaffolding on which Nigeria would eventually negotiate independence. English became our language of statecraft; Westminster became our institutional model; British universities and military academies trained generations of Nigeria’s future leaders, bureaucrats, soldiers, and diplomats.

The result was not blind loyalty, but familiarity — a shared mental map of governance, law, diplomacy, and global orientation.

The Civil War and Britain’s Strategic Choice

In our darkest hour — the Nigerian Civil War — it was Britain that stood by the Nigerian state. While the conflict remains emotionally charged and its scars still tender, one strategic reality endures: Britain perceived Nigeria as too important to fragment. A stable, united Nigeria was considered vital to African balance, Commonwealth cohesion, and Western influence on the continent.

London did not support Lagos merely out of sentiment. It acted from interest — recognizing Nigeria as a geopolitical anchor capable of shaping Africa’s fate. That wartime decision deepened strategic alignment and reminded Nigerian leaders that sovereignty and unity need allies with long memories and strong institutions.

A Long Arc of Affinity

Post-war, Nigeria and Britain continued a relationship marked by:

• Military and intelligence cooperation

• Deep educational and cultural ties

• Mutual commercial interests

• Shared democratic traditions

• Significant Nigerian diaspora presence in the UK

• Commonwealth bonds and security coordination

For decades, Nigeria broadly functioned within the Anglo-American geopolitical orbit. This did not denote subservience; rather, it reflected history, training, networks, interests, and the comfort of longstanding diplomatic muscle memory.

The Quiet Pivot — and Western Unease

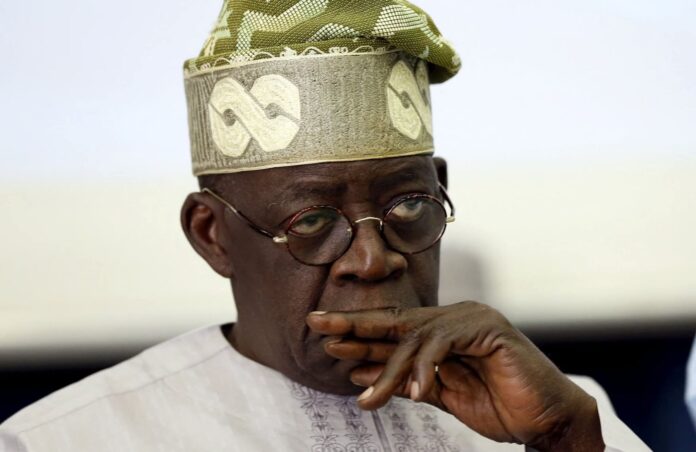

Yet foreign policy is never fixed. With the advent of the Tinubu administration, Nigeria’s diplomatic posture has shown a distinct tilt toward France. Longstanding Lebanese commercial intermediaries and a deepening of political and financial ties with Paris have accelerated this shift. Frequent presidential visits to France, French commercial forays into Nigerian sectors, and quiet expansions of Francophone strategic influence signal a re-balancing.

In global politics, such shifts do not pass unnoticed.

Where Britain — and by extension the United States — once enjoyed near-undisputed primacy in Nigerian affairs, Paris now appears to be advancing. And great powers rarely yield influence without resistance.

Thus a question arises: Is some of the current hostility toward Nigeria in Western capitals — particularly Washington — rooted not only in concerns about governance or human rights, but also in anxiety over the loss of strategic foothold?

Nations act based on interest — not affection, not sentiment, not morality. A Nigeria leaning too close to France unsettles old partners accustomed to Abuja’s predictable orbit.

The Task Before Nigeria

No nation should confine itself to one axis of power. Diversification is healthy. France, Britain, the United States, China, the Gulf states — all can be useful partners if Nigeria negotiates from strength, confidence, and clarity.

But a pivot executed without finesse risks provocation.

Nigeria must:

• Secure its independence of action

• Avoid signaling abandonment of old partners

• Communicate strategic intent clearly

• Prevent foreign rivalry from turning our soil into a chessboard

Foreign policy is chess, not checkers. Silence speaks, gestures matter, visits send messages, and alliances — old or new — have memories.

Nigeria must chart its course responsibly, without losing sight of the anxieties it awakens in old friends or the ambitions it stirs in new ones. In diplomacy, perception can spark backlash — and sometimes, what looks like moral outrage abroad may in fact be geopolitical pushback dressed in ethical robes.

In a multipolar world, Nigeria must be neither pawn nor trophy — but player.